RE-RANKING STEPHEN KING:

MY FAVORITES, LEAST to MOST,

the 2016 edition

I figured it was high time to patch up the Official Dog Star List of King Favorites.

I've re-read several Kings over the past few months: The Tommyknockers, It, The Stand, Salem's Lot, From a Buick 8, The Shining, and I'm currently re-reading The Regulators. All for the hell of it/ personal-enjoyment, not really with the idea of blogging anything about them. But as I've suspected several times over the past few years, my 2013 rankings do not reflect my King sensibilities of 2016. Which makes sense: prior to 2012, I hadn't read any King since the 80s, pretty much, when he was my absolute favorite author. Since 2012, though, I've read everything except Lisey's Story (which is why it's not included below - just couldn't get into it and am saving it for the proverbial rainy day) and the two Straub collaborations (ditto) plus dozens of interviews and reviews and re-visits and re-reads and re-watches, yadda yadda.

So, a revised list seemed like a fun thing to do. Hope you agree. Feel free (in fact, consider yourself downright invited) to tell me where we disagree in the comments. (I'm still shaking my head at the Vulture list that kicked off the whole King's Highway project to begin with. The nature of horse races and all that, but our areas of deviation are great.)

Not included below: non-fiction, or short story/ novella collections. I wanted to keep this strictly to novels. If I had elected to, though, you'd definitely find On Writing, Different Seasons, Full Dark No Stars, and Night Shift in the top 20. I decided not to link to any previous reviews, as I didn't want to come up with dozens of ways of writing "As I wrote in my original review..." Plus, too many hyperlinks - you know where and how to find them all. All of this has happened before and will happen again.

Where pertinent, I quoted myself. Not because I'm especially quoteworthy, just to either highlight where my opinion changed or because why-reinvent-the-wheel-eh?

53.

|

| (2004) |

Many King fans have been angry with the news that Idris Elba has been cast as Roland in the upcoming Dark Tower movie. Not just that bit of casting but other news of the production has led to the probable conclusion that what will appear on screen will be as removed from the source material as, say, the Under the Dome adaptation, or worse. I'm sure it will be very different, but my question is: is that in and of itself a bad thing? I'll put it another way: if the books were put on screen verbatim, they'd be a disaster.

My opinion on that has changed somewhat since I originally made my way through the Dark Tower Suggested Reading Order. I do like the very, very ending of the saga (in book 7), but there's an awful lot that I just don't like or even think is all that good in getting there. Song of Susannah encapsulates 80% of it. An ill-considered and irritating read with a few bright spots, I have no qualms nominating this as King's sloppiest book.

52.

|

| (1996) |

There's actually a few things I really like in this book. It's an irresistible set-up, for one, and the opening really grabs you. And I like how this and The Regulators appear as "twinners" of one another. (Although I don't think the idea was altogether successful.) And Johnny Marinville is a pretty good example of that-guy-King-protagonist.

While I'm praising the book, I think Desperation is probably better than the next four or five on this list. But the bottom line is it's just too damn long. For that alone, it comes in second-to-last. This could have been a cool novella and instead we get leviathan. I get the sense even King was sick of it about halfway through.

And while I appreciate King's trying to write a serious exploration of dark religion/ God, etc., he does not succeed here. The compelling insights end up smothered by the mundane ones.

51.

|

| (2014) |

That this book won the goddamn Edgar Award for Best Novel blows my mind. As a novel, it's the strangest and most-tonally-off episode of Barney Miller ever.

50.

|

| (2016) |

The conclusion of the trilogy that Mr. Mercedes began is equally unpalatable for yours truly - and for more or less the same reasons: cliched characters and scenarios, pandering, lazy writing, and unconscious (I'll be charitable) swipes from his own earlier material (but, as always, a "way to go, champ!" shout-out to his editor in the Author's Afterword, proving for the umpteenth time what I imagine an editor does and what an editor actually does must be completely different things) - but it gets the slight edge over that one because some of the mental possession stuff at least engaged my imagination. (Even if it seemed a swipe, too, from The Regulators and Dreamcatcher and elsewhere. But hey.)

49.

|

| (1983) |

This one is at least short. It's not bad - I like the idea of King writing a werewolf story, certainly, and I used to love Silver Bullet when I was in 7th grade. But this is like the Cliff's Notes for a novel King saw in a dream, or something, not fleshed out enough to really be compelling.

48.

|

| (2005) |

I actually like this one - it's engagingly written and all. I just can't fathom why the hell he wrote it. An anti-mystery mystery/crime novel is an interesting classroom exercise, I guess, and he does it reasonably well. But... that's kind of the point: how would you know if he did or didn't? Anyone can create a mystery and chop it all out into lines of dialogue and then fail to solve it.

Of course, not just anyone can make those lines of dialogue enjoyable reading. Which King can always do. But that's what I mean - is that why he wrote it? To show off? I doubt it. So... what's the point of it? Is this like one of those abstract "my kid could do it" paintings that is all-context? I'll have more to say on this when we get to From a Buick 8, but here's where this one falls for me.

47.

|

| (2004) |

I like the very, very ending of this one. Everything else, not so much. And some of it - like the Crimson King ("EEE-EEE!") and the Bryan Smith/Stephen King stuff - I really don't like. That it's a long-ass book that ends the whole saga magnifies these problems.

But like I say, the very, very ending with Roland the tower, that works for me. And that is sometimes all it takes for me to be more positive on something than I otherwise would be. I guess that goes for the whole Dark Tower saga and not just Book 7.

46.

|

| (2013) |

I think this book is mostly a failure. It just doesn't work the way it should. He claims he wrote it as a challenge to himself. I wish he'd have challenged himself a little bit more. But as with The Dark Tower, the very last few chapters (once the frustratingly-non-threatening True Knot are finally put out of their goddamn misery) are good.

That said, if Howard Derwent and the ghosts of the Overlook wanted Dan as their own psychic-augmenter in The Shining, aren't he and Abra delivering an equally-powerful conduit to that purpose to them in Doctor Sleep? Someone mentions the possibility and shoots it down, but I almost wish they hadn't brought it up, as that idea was way cooler than what I was reading.

45.

|

| (2007) |

Not a bad read at all, but it's the sort of thing a young man writes when he's channeling other authors rather than writing anything original. (In this case, I'd say Of Mice and Men and In Cold Blood.) It's interesting that he sent this to Bill Thompson alongside Salem's Lot way back when and that Thompson chose Salem's Lot. Who knows what King's career might have looked like had Blaze been the follow-up to Carrie? (Probably the same, but who knows.)

44.

|

| (1977) |

Another younger-man's-book. Not that that's a bad thing, just that it feels dated. Then again, I'm turning 42 this year, and with each passing moment the rage and narcissism of adrenaline-filled adolescence is more and more alien to me. That said, I can throw on "Kickstart My Heart" and get a much more palatable dose of it, and with fewer pretensions.

43.

|

| (1981) |

In On Writing, King mentions that he has no recollection of writing this novel. I suppose on some level I am impressed by this. (Speaking of Motley Crue.) Putting together a coherent narrative, never mind a best-seller, in the midst of an epic-drunk blackout is certainly a feat. But I agree with Harlan Ellison: this one is "just okay." The kind of book 2-star reviews on Goodreads are made for.

42.

|

| (1983) |

I really loved this book when I read it in junior high. But not so much as an adult. I wonder why that is? Because I wasn't savvy enough a reader in junior high? Or because King captured a particular slice of adolescent malevolence and fear and recreated it well enough where my younger self could relate where my older cannot?

I'm not 100% sure. So let me quote myself. "There is no real dramatic tension; the insights into adolescence, parental/familial relationships, girlfriends, and sex would be no one's idea of 'the definitive portrayal of...' such. Again, not that they're bad, just that they're functional and that's about it. They're as believable as they need to be, but all of it could be cut-out or diminished with no harm done.

41.

|

| (1974) |

King mentions it as "a young book by a young writer. In retrospect, it reminds me of a cookie baked by a first grader — tasty enough, but kind of lumpy and burned on the bottom." That's how I feel about it, too.

Whatever the case, I'm not a huge fan of the inquest-framing-mechanism, nor the sudden development of a psychic connection between Carrie White and Sue Snell.

Movie's way better. De Palma's, anyway. (ducks)

40.

|

| (1987) |

As with Christine, I remember just loving this one when I read it in junior high. But there's really not much going on in it.

Near the end, King writes that Thomas and Dennis do meet and do battle with Flagg again but that is "a tale for another day." I doubt he'll ever sit down and write that, but fingers crossed. (Ditto for The Further Adventures of the Tet Corporation aka "The Old Farts of the Apocalypse.")

39.

|

| (1998) |

Many people love this book, but I just think it's King on autopilot. That said, I wonder if my impression of it would have been different had I read it before I read Duma Key. It's possible - the two works share some thematic and structural overlap. And maybe this one just seemed like a poor-relation of Duma Key to me, but would it had I read the works in order of publication? Don't know.

One thing on which we all agree: the mini-series was dreadful.

38.

|

| (2001) |

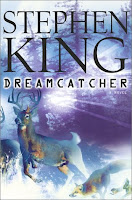

Another one I rated much higher than other people when I originally read it, but I've walked it back somewhat. Dreamcatcher reads more like an attempt to "fix" The Tommyknockers by grafting parts of It onto it. It has its moments - more than a few of them - but it's a bit of a mess. (Two words: "Shit Weasels." Two more: "I, Duddits!")

It benefits from having been made into an unfathomable trainwreck of a movie. Compared to it, the book reads like To Kill A Mockingbird, for eff's sake.

37.

|

| Gerald's Game (1992) |

Well, here's one that was practically in last place when I ranked these originally. I still think it's not altogether successful, but I appreciate that King made the attempt. It's a miss for me, but an interesting one. The epilogue is the fatal blow, I think, but many disagree. So it goes.

In my original blog on this book, I'd taken issue with the eclipse-crossover-stuff with Dolores Claiborne. (I felt - and feel - it didn't work.) A commenter left this succinct rebuttal: "I think crossover works perfectly. It is one of my favorite crossovers."

Not sure why, but that amuses me. I think it's the better-hop-on-the-bus-Gus-ness of it: "You got it wrong, Jack. I'm done."

36.

|

| (1989) |

If Gerald's Game is a noble failure, The Dark Half is an overly cautious success. I wanted to write "ignoble success," but I don't think The Dark Half is lacking in merit. Just that it's King not taking a chance, really. It reminds me of the album a band puts out when they want to assure their audience that they remember why they're fans. Nothing wrong with it, but it can sometimes lead to unexciting material, despite resembling the material you love. If that makes any sense.

In a sense, I admire something like Gerald's Game (or even Lisey's Story) more, because it's good to see King pushing himself in other directions.

35.

|

| (2015) |

I agree with this review on Goodreads re: the Hodges trilogy overall but most especially re: Finder Keepers - this would have been a better stand-alone book had King not felt he had to cram it into the larger Brady/Hodges story. Divorced of the failings of the trilogy, though, it's a pretty good story, and Morris and Saunders are far more interesting (and original) characters than anyone in Mr. Mercedes or End of Watch.

34.

|

| (1984) |

I'd love to see a proper film of this book. The story itself is far more cleverly written than anyone who's only seen the movie (or only knows the basic concept) might think. A quick page-turner that resolves itself logically.

33.

|

| (2003) |

Another one that I really enjoyed while reading but has fallen a little the more I think about it. Mainly due to where the story goes from here, forcing me to ask questions about this one that I hadn't when originally reading. But it's still an absorbing read, to be sure. (That picture of Susannah on the cover, though, is awful. I mean, she doesn't even look human in that pic. And the font/ typeset is so garish. All in all, the art design of the whole Dark Tower series gets more wrong than right, unfortunately, and with the talent they had working on it, that's criminal.)

32.

|

| (1979) |

My opinion is more or less unchanged from my original review: "King has said that he likes the movie better, and I agree. The changes in the material (from adapting it to the screen) definitely work to the story's advantage. The relationship between Sarah and John is more romantically-doomed as it stands in the film, as is the undoing-of-and-apocalyptic-visions-pertaining-to-Stillson scene(s). I think the book is good, don't get me wrong. I just like the way the film handles the elements better."

31.

|

| (1987) |

and

30.

|

| (1991) |

both have their strong points. I mean, we're ahead of The Dead Zone in our countdown, and that's a pretty damn good book, so from here on out we're in solid-RBI-and-extra-bases territory. (Have been since Finders Keepers, actually.) Drawing of the Three has a lot of rough spots, but damn if it doesn't draw you in and keep you close from start to finish. I'd say it's largely because of Drawing that the reader cares about the ka-tet in every other book.

And in The Waste Lands the build-up and revelation of Blaine the Mono is some of my favorite King all-around. (The Tick-Tock Man, decidedly less so.) As is "Velcro Fly" playing forever over post-apocalyptic New York ("Tull") with slow mutants and rocket lasers and what not. Seems about right.

The only sticking points for me are larger-series-related. I'll stop writing that now, since I've well-established my feelings. But yeah, some of the mythology-related stuff, specifically, becomes like the mythology episodes of X-Files - I tune it out or it decreases in importance to me, as a result of my problems with books 6 and 7.

While this novel doesn't enjoy the greatest reputation, I find its uniquely-Kingtastic take on the more misogynist aspects of Greek mythology to be pretty interesting. I could have gone for a bit more on that side of it and less on the Indigo Girls - and interesting parallel with Insomnia and the big abortion-rally convention center thing - but it's still an interesting work.

Without that angle, it'd be a rather stacked-deck affair with your typical King villain (racist, misogynist, obsessed-beyond-all-realism with beating his wife) eventually undone by his own lack of other character traits.

Perhaps it's a failure, but it's an interesting one, and I tip my cap.

28.

Often forgotten or undervalued, it seems to me, but what can I say? There's nothing to cut or re-arrange. Like it or dislike it, it's a pretty lean book that holds to its own inner logic pretty well.

I only wish King had elected to write a sequel to Firestarter instead of The Shining.

27.

|

| (1983) |

This is a harrowing read, steeped in moral relativism and American Gothic Horror. I don't think it's perfect, but it works because it doesn't cheat: it ticks off each box of said genre with no apology and doesn't let you skip over any of the nitty-gritty. The sudden manifestation of a child with psychic powers in the latter pages is always unfortunate, but overall I'm positive on this one, mega-downer that it is. It's like a negative print of A Christmas Carol, where Scrooge gets the visitations but does not grok the true meaning of Christmas, so it becomes some horrific inversion of itself where resurrection is horror instead of salvation. (And Tiny Tim gets run over by an 18-wheeler.)

26.

|

| (2002) |

Here's another one that is placing much differently this time around than where it did the first time (in the top ten.) I still find it a very enjoyable read, but upon re-examination, I found myself agreeing with this Goodreads review:

"King

spends a great deal of this book explaining to the reader that there's

not always a definitive ending. Listen, friends and

neighbors, I can get behind a short story or a novella that leaves me

with an unsatisfactory ending because they aren't time sinks. To be in

the audience of a magic show wherein the magic is only alluded to is a

terrible trick. I don't need everything explained. I don't need my hand

held. But I want a complete story. This is not a complete story. (...) The shifts in tone are jarring. You never know what kind

of book you're reading. The characters are taken part and parcel from

The Green Mile. If you've read both books, you'll probably see where I'm

coming from. I mean even down to the wild fucker named Billy. Billy the

Kid... Billy Lippin. And Sandy Dearborn and Paul Edgecomb are the

same person. I don't care what their names are. Sweet baby Tom

Cruise, the parallels are so obvious..."

I guess they are! Though: they didn't occur to me at all while reading. Now I can't un-see it, though.

Mostly, the reviewer is right - it's kind of silly to write a book-length Shaggy Dog story about the non-point of Shaggy Dog stories. I get that the whole thing is a metaphor of life and death and the mystery of both, that the anger that Sandy feels towards Ned for his impatience and youth is fear of the unknown and deep primal urges to eat our young. (Wait, what?) But perhaps these are truths that don't fit so snugly in the not-quite-car of the title.

That said, I find the evocation of the barracks and the mystery of the car in Shed B very enjoyable reading. (And likening it to a magic show where the magic is only alluded to is not quite accurate; it's more than alluded to. The magician just doesn't explain his trick. That seems important enough of a difference to underscore.)

25.

|

| (1982) |

It would be a real shock to people, I bet, if someone made a faithful film out of this book. The Schwarzenegger film is a dubious classic - the kind of film people love to remember and watch with friends but nothing anyone would mistake for a quality film. (I hope.) It also has very, very little to do with this disturbing and kinetic slice of dystopian sci-fi fatalism, one where the protagonist - holding his intestines in place with one bruised hand - pilots the jet-airliner he's hijacked into the skyscraper headquarters of the media conglomerate that rules future America at the end.

Like all the Bachman books, it'd have made one hell of an American New Wave film.

24.

|

| (1982) |

(2019 reread here.) A pretty surreal read. I wonder how the Dark Tower saga would read if each entry was written in this manner. Kind of pointless to speculate on such a thing, but pointless-speculation is my specialty. The whole thing with the Dark Tower is it's about different worlds, different levels of the Tower. This actually reads like you're reading King from a different dimension - familiar but alien. This quality fades over the rest of the series, but it's the main appeal of bk 1 for me.

23.

|

| (1999) |

I know this book bores some people, and I can totally see why. It's already short but maybe it could be even shorter. I think most of my affection for it comes simply from having hiked the same woods - and gotten lost in them and prayed to / feared the same God of the Lost - as its protagonist. More than once. A silly reason to like a book, I grant you, but also one any reader can relate to, I'm sure.

Nevertheless, I think if someone was trying to write a book on King's concept of God, this would be an important go-to. (And unlike Desperation, you don't have to dislodge a two-ton boulder worth of extraneous text to get to it.)

22.

|

| (1992) |

The more successful of the two In the Path of the Eclipse books, for my money. Not the easiest subject matter - and maybe it's a better-realized film than a novel? - but a solid piece of writing and narrative voice.

21.

|

| (1981) |

This book is a genuine surprise. I don't know anyone who's read it who doesn't rate it a lot higher than its reputation might suggest. It's a very honest book, written during a particularly painful period of time in King's life. (The death of his mother).

What is it about it that works so well? I might have to do up a whole entry on this one, too. The King's Highway Bridges and Infrastructure Renewal 2016 Tour adds another connector byway!

20.

|

| (1996) |

This too is part of said Infrastructure Renewal Project, so I won't say too much. But few champion this book, and I'm not sure why. This is King synthesizing much of his career up '96 into one blood-soaked, kinetic scenario: autistic child, possessed by a dark entity with fantastic psychic powers, utilizes the elements around itself (a show/ action figure-set called MotoKops 2020 and "her dead friends on TV" i.e. old, violent westerns) and wreaks unspeakable havoc on a tightly-drawn group of everyman/everywoman survivors.

Its insights into TV-violence and TV in general are perhaps not as provocative as they want to be, but they're compelling just the same. This could be the craziest film ever made! Whichever candidate vows to greenlight its production gets my vote.

19.

|

| (2012) |

A piquant aftermint/ prequel to the Dark Tower saga. Three stories for the price of one, with the central one of young Tim being the heart of the story. Am I ranking it too highly? On the contrary, I think quieter books like TWTTK will be the most enduring of all King's work in the years to come.

18.

|

| (2013) |

A fantastic nostalgia piece from King, only slightly sullied by the appearance of yet-another-kid-with-psychic-insight - something that could have so easily been excised from the narrative - and on the heels of that, a huge-ass storm at novel's end. It makes me seriously consider whether or not King's success comes from a compact with some demon or faerie-folk whose only stipulation is to end everything with a storm and psychic child.

Regardless, this one "lights" everything that comes in the path of its narrative eye with just the right touch. I like this side of King perhaps more than any, his "Summer of '69" or "In Your Wildest Dreams" side. King combines all the heartbreak-recovery-summer-I-grew-up narrative with a very believable recreation of a bygone-era amusement park. Good stuff. I can even see this being taught in classes of the future, so easily does it evoke a very specific slice of the past/ all our pasts.

17.

|

| (1986) |

Look, let's be honest: this book really could have used an editor. There seems to be some denial on this topic in the King community, and from the man himself as well.

What we have here is some of the best writing and structure of King's career, surrounded by a few interludes too many, one character (looking at you, Stanley Uris) too many, a few Bowers-outbursts too many, a few too many stutters, a few too many plot-convenient manifestations of telepathy, and a few (thousand) too many "Beep Beep Ritchie"s. It all adds up to three or four hundred pages - not chump change - that could and should be lopped off.

And then of course there's the notorious ending. Which, needless (?) to say, doesn't work - not for puritanical reasons, though that case can certainly be made. It doesn't work because it makes no goddamn sense. And yet, then as in now, judging from the things I read about It, everyone just kind of shrugs and accepts King's completely unsatisfying explanation that the preteen sewer gangbang that "binds the characters" is just "another version of the glass tunnel that connects adulthood to childhood."

It's such an odd evasion for an obviously-batshit scenario. All it would have taken was one trusted friend to point out the lack of preteen sewer gangbangs in every work of art ever made. "Surely you can see this, right, dude?" Meh. The ship has sailed.

King threw open the windows and wanted to make a book about everything: racism! nostalgia! childhood! imagination! more racism! sizeism! cosmic balance! the 50s! the 80s! riddles! cocaine! booze! writing fame! show biz! more coke! God! Anti-God! history! Bangor! America! the twentieth century! incest! bullying! child abuse! teenage reacharounds! hoboes! you name it. It almost never works to mash down every button on the board. That It actually almost pulls it off is nothing short of amazing. But: it doesn't. (That so many think it does work is evidence of how well-written so much of it is.)

So, here it is at #17. Truthfully, any book that sticks the landing the way this one does, after 1000 pages, deserves to be punted even further down the line. Except well, like everyone else, the parts of It that work for me really really work, and I still kind of love it.

16.

|

| (1994) |

This one also suffers from some bloat - and a bit of a confused ending where altogether too much is made of the Susan Day character, who is treated like some kind of rockstar for hundreds of pages but then is kind of shuffled off-screen, her importance never quite justified or fleshed out. And its Dark Tower overlap might be too off-putting to some, as might all the old-people-sex. (I still have no goddamn idea why the Crimson King was even interested in Earth, much less Patrick or anything happening here. The whole rose-and-Breaking-Beams thing seems so arbitrary. But hey, "he's evil! He's crazy!")

Nevertheless, Insomnia is a moving meditation on death and the joker-in-the-decks that beguile us on our way to it.

15.

|

| (1987) |

A great and compelling novel made even greater and more compelling by the revelation in On Writing that "Annie Wilkes is coke, Annie Wilkes is booze, and in the end I was tired of being Annie's pet writer." The novel-within-a-novel that Paul Sheldon writes in captivity is almost more instructive than the one King writes.

14.

|

| (2014) |

I've flipflopped on where to place this a few different times, but after much reflection, I feel reasonably certain this is where it shakes out at least for me. I love the bleak ending (earned, too, which makes its aftermath all the more horrifiying), the characters, and the time-sweep of the whole thing. A strong late-innings home run from Sai King.

13.

|

| (1978 / 1990) |

The Stand is two different books. Both are insanely readable, but they do not (for me) occupy the same space as gracefully as they could. One is an ultra-realistic character study of a society in breakdown and recovery, with micro/macro managed adeptly. The other is a pulp religious parable where characters receive their instructions from dreams and a retarded man is put under deep hypnosis to become a spy and God speaks through burning bushes and stuff like that.

I don't mind either book - I don't exactly mind their co-existing under one cover, for that matter - but I can't in good conscience say this is King's best work. The two books just don't reconcile themselves as masterfully as a truly great work should.

An anonymous commenter at The Truth Inside the Lie's review of the miniseries points out another conflicting-voice problem with the revised (1990) edition of the book and addresses some of the problems current and future audiences might have with the material:

"I've just been reading the 1990 version of the novel for the first time, having grown up with the original in the early 80's, and, despite the hype of it being King's 'original intention', large chunks of the text seem to come from somewhere else (...) The 70's voice is more idealized and poetic, the late 80's voice is more cynical and believes the post-modern 'ugliness is truth' cliche. The two voices are fighting throughout the text and it weakens the novel.

The Stand is a 70s Work, as perfect a summing up of the political climate of the 70s and its related apocalyptic fears as one could hope for, which explains its popularity at the time. (...) By moving the timeline further into the future, King's world stops making sense and reads utterly-false. Flagg's radical underground network is long a thing of the past by 1990. Student radicalism had become nonviolent and the ex-Hippies had all become Yuppies through the 80s. Larry - let's be real here - Larry is a poorly-disguised 70s Bruce Springsteen - and would have been all over MTV and easily-recognizable. Rita's 'mother's little helper' addiction is a 70s holdover. Frannie's discussion of abortion, the preciousness of her mother's parlor and her concerns over what the neighbors would think - to the extent of sending her away until the baby was born - ring particularly false in 1990. The final payoff is the grand 70s / early-80s fear of death by nuclear destruction, one that was pushed out of the cultural boogeyman spotlight by Reagan and Gorbachev's disarmament treaties in Glasnost.

If these themes didn't truthfully resonate across the 12 years between the first version and the uncut version, can they still resonate with a modern audience?"

All good points. And yet: I love it. I don't know anyone who read it as a teenager who doesn't. (At least of my generation.)

12.

|

| (1979) |

I know at least one reader who considers this King's worst book. Needless to say, I disagree. Outside of The Gunslinger (and perhaps Lisey's Story, though I wouldn't know, would I?) this is King's most surreal work. I know exactly how the American New Wave version of this film should look, and everytime I read it, the film plays in my head. Very frustrating! But whenever they invent the machine to project films straight from someone's head, you're in for a real treat.

11.

|

| (1991) |

Kevin Quigley referred to this one as "not only a terminal point for one of King's favorite fictional places (i.e. Castle Rock), but also a hub for his favorite dark fascinations." Namely mental illness, class and gender inequality, pedophilia, suicide, magical strangers preying on a small town's vulnerabilities, as opposed by an ordinary guy and gal in over their heads who may or may not have some help from God/ turtles.

Not the best of King's town-under-siege stories, but it's a damn finely-constructed work. King's stock characters are all well-drawn. If you bought this from a catalog, it would arrive in perfect working order and as described and last you a lot longer than you ever figured.

10.

|

| (1996) |

A now defunct blog (written by Steve Kimes) described this one succinctly: "a wealth of plot, a mix between the real and the mystical, excellent characters." It's all that and more - some of King's warmest writing. (Another source to mine for King's attitudes re: God/ the Great Beyond.)

9.

|

| (2009) |

My personal vote for the best political satire of the Bush/ Cheney years, by any American author, in any genre. (Having it be the Corgi (Horace Greeley) that gets the convenient psychic powers was an unexpected touch. You rascal, you!)

8.

|

| (1975) |

A funny thing happened as I was re-reading this a couple of months ago. I kept dog-earing pages I intended to cite as evidence that King has grown quite a bit since his first town-under-the-siege books. Yet, when I went back to them after finishing, all of them seemed to prove that I was wrong - he was just as good at it then as he is now. Salem's Lot is a traditional vampire tale as mixed with Peyton Place. As with ISIS or whomever exploiting our existing domestic problems to wreak havoc, one dedicated vampire and his capable assistant (both of whom are combined into Leland Gaunt in Needful Things) exploit the crap out of the pre-existing conditions of Jerusalem's Lot, Maine.

7.

|

| (2006) |

Some people really hate this book. These people are nuts. If you are at all literate in what King does, you must recognize that this one is the Matisse painting of King's catalog - everything's bold colors and stripped down to its essential lines.

Plus, as we go further and further into the internet age, the idea of society descending into weaponized chaos - equalized at last in pure hivemind-y hatred of "the other" - as triggered by some ghost in the machine seems less and less sci-fi and more just like everyday life in 2016, especially the false-reality that invades your brain and overrides even your desperate desire to escape.

6.

|

| (1987) |

It was written more or less at the same time as this one (and enjoys) the greater reputation, with Tommyknockers looked at as its Cocaine Album cousin. I think that should be reversed - It is the cocaine album and The Tommyknockers is the unsung punk-rock opera of King's bibliography.

5.

|

| (1999) |

A surprising and poignant collection of a few short stories and a novella, all connected thematically and sharing some characters. A beautiful little book. It aims at poignancy and nostalgia and hits its target(s). The short stories, far from being filler, complement "Low Men in Yellow Coats" (for my money, among the best of King's early-childhood-era recreations) perfectly.

4.

|

| (2011) |

That people routinely refer to The Stand as his best work when he has this so recently in his rearview must drive King crazy. Great characters, great pace, great construction, and great heart. A re-read will illuminate all the ways the recent Hulu adaptation went off the rails when it tried to compartmentalize and/or take shortcuts (or flat-out change all-important details with the Yellow Card Man/ nature-of-goddamn-reality.)

3.

|

| (1997) |

An oddly-constructed book. It begins by ending the last scene of The Waste Lands, then wanders into The Stand (on some level of the Tower), then goes into a long flashback as Roland recounts the tale of his most tragic adventure. And within that tale is some of King's most emotionally harrowing and earned work, hands-down.

If the movies get nothing else right, let them at least do Wizard and Glass half-decently.

2.

|

| (1977) |

I will be revisting this one in more depth sometime soon. Suffice it to say, this is early-King at his best. Hitting on all cylinders. It amuses me to think Bill Thompson tried to talk him out of writing it, so he wouldn't be typecast as just a horror author. I mean, fair advice - I guess he was typecast as just that for quite some time. Still is by some, though not by anyone you should, like, listen to. Thankfully it was advice he didn't take, though, and America acquired a new home-grown horror classic.

1.

|

| (2008) |

If you line up every trope you could possibly associate with King, they all combine wonderfully in Duma Key. Just the right amounts of each are used.

Some quick and by no means exhaustive examples: there is a big-ass storm at the end, sure, but it makes thematic sense and isn't just found-structure. There are characters who receive temporary, plot-convenient psychic insight, but there's just enough covering fire to excuse it. "Haunted racism" is a factor, but no one goes into cartoonish Brady Hartsfield/ Henry Bowers territory. And artistic creation / malevolent possession-and-disconnect are linked and explored, but this is not a novel that is about creative narcissism the way The Dark Half or "Secret Window, Secret Garden" are. Nor does it approach that topic the way Misery does. This is new terrain for King, even if it feels so familiar.

Beyond that, it's simply a beautifully written book, shocking at turns, and airtight as hell, all while feeling breezy even at its expansive size. It's for all these reasons I consistently nominate it as King's best book and probably my personal favorite as well.

I don't know why I seem to be the only person to do so, but after revisiting the work several times now, I stand by the assessment.

~

How about you?

NEXT: The Best of the Miniseries