"This is not a volume about Columbus' crossing, and not in any clinical sense even a volume about our own Atlantic crossing. The ocean passage serves as a spinal column, but the book is primarily a tribute to people and to institutions that have nourished me for many years; so many years now that (the by-line to this book is) I speak of the end of the affair, not knowing whether I will set out again to cross an ocean, knowing that I will never again serve, as I did for so long, as editor in chief of the journal I engendered, and love; increasingly aware of mortality (and) of the fragility of even the most intimate associations.”

In 1990 William F. Buckley Jr. and friends set out from Portugal, bound for Barbados, on their fourth transoceanic passage (“Ocean-4”). This account of the voyage, Windfall, was published in 1992, and he groups it along with the other sailing books and two others like this in the front of the book:

This is the first and I believe only place these works are grouped under that particular header. It gave me the idea to go back and reread them through that lens. Mainly it was an excuse to reread them. I figured I’d start with the last of them – why not? – and then go back. So here we are.

The above, from reading them all the first time to the re-reads to sketching out the plan, was 2018 until just a few months ago. Things move slowly and swiftly in alternating currents round these parts.

~

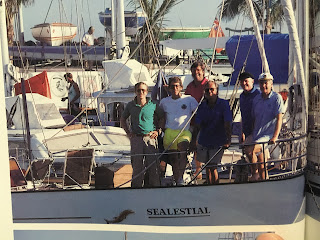

All but the first of these transoceanic voyages were done on the Sealestial, a seventy-one foot long racing ketch built in 1973. If you've seen the movie Dead Calm (referred to bafflingly as White Calm here) the Sealestial is built from the same prototype of the Stormvogel, the boat used in that movie. Its owner, the mysterious Dr. Papo, remains off-camera throughout the books. More on him later.

- Bill, of course, pardon the familiarity. Captain of the enterprise in all ways but one (his agreement with Dr. Papo on chartering the Sealestial: if the official captain, Allan Jouning, disagrees on any course of action that might imperil the Sealestial, it is understood that Bill will be overruled). WFBJR led a unique to say the least life. As he writes re: a dinner party with James Clavell and his wife: "In the ten weeks since I last saw you, I have played two harpsichord concerts, I've retired as editor of National Review after 35 years, I've crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a sailboat, and I've published two books, one fiction, one nonfiction, and I have become a senior citizen."

- Van Galbraith, Reagan's ambassador to France, on the board of directors for Moet & Chandon, Morgan Stanley, National Review, Club Med, college friend of Bill’s.

- Dick Clurman, “the most organized man in the world,” “the man born to cut Gordian knots”, former chief of correspondents for Time/Life, author of the excellent Beyond Malice, college friend of Bill's and Van's.

- Christopher Little, hired as the professional photographer for Atlantic High and earlier sails, fellow Yalie, former EMT/Chief, former Miss America Judge, and, most recently, mystery writer.

|

| All pics, I should mention, were taken from my phone from the book, under varying light (and kids chaos) conditions. Sorry for the imprecision. |

- Tony Leggett, a former Olympic sailor introduced to Bill and the gang after Louis Auchinchoss read Airborne and arranged it. Still at it, year later.

- Danny Merritt – a vital protagonist of these sailing books, Christo’s childhood friend and subsequently Bill’s, father of the founders of Nine Line Apparel, which has an admirable backstory. But his progeny aside, info on Danny is kind of hard to come by on the web. Unknown on the internet but immortalized in print by WFBJR? Sounds like a pretty good deal to me.

I mentioned Allen Jouning up there, a professional sailor, one-time captain of William Simon's superyacht the Freedom, longtime associate if Bill et al's, New Zealander, possible walrus-man.

In the Canaries - roughly the halfway point - Dick and Danny fly back to the States, and their berths are taken by Christopher “Christo” Buckley, (son, author, journalist), Bill Draper, international financier and muckity-muck, longtime friend of Bill et. al's "since we were inducted into the same society at Yale", and Douglas Bernon, a friend of Christo’s and husband of Bernadette, onetime editor of Cruising World.

|

| Christo, and Liz, the chef. (She had her own exclusive part of the ship.) |

SOME HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE TRIP

Prior to leaving, Bill runs into Jack Paar in the hotel bar in Portugal, twenty-eight years after their (quite mild in retrospect) dust-up written about in Rumbles Left and Right. They exchange pleasantries, and Paar compliments Christo's latest book, a compliment always appreciated by any father/ literary family, I assume. Nice to see this and another nice bookend for Bill's career.

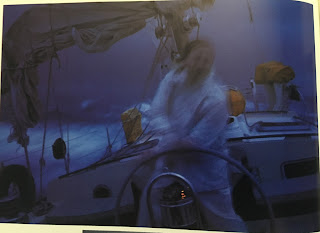

However, if such a thing is a good omen for the sail, it falters quickly, as two days from shore they hit the worst storm anyone aboard has ever experienced.

|

| Some great storm reading in this stretch. |

Reaching Funchal in Madeira, they don't think much of the Casino Park Hotel, of which Christopher Little writes: “(it) had about as much Old World Charm as Donald Trump.” Good line and a bit of chuckling portent, there. Speaking of, elsewhere in the book, Buckley mentions having been recruited by Roger Stone in a bit of Machiavellian electioneering in CT, trying to persuade voters to send Rowland (a bad guy) to the Senate in order to keep Weicker (a worse one) from winning, resulting in Joe Lieberman's victory. That plus the Donald Trump line made me laugh - good thing Bill was getting out when he did. Stormy weather and the shape of things to come!

After that, back at sea, they are shadowed by a phantom ship for awhile, possibly a drug pick-up (they speculate), and then they cross the path of the Eagle, which is the Coast Guard cadet ship. “Two sailing ships, one with its sails full, the second headed into the wind under noiseless power. The cadets’ cameras popped in the night, opposite our own doing the same thing, a ghostly simulacrum of cannon flashes exploding at each other at sea.”

Christo brings correspondence and papers, so we get a lot of that (Bill is forever answering letters or cross-clipping from columns, etc.) for the remainder of the book, as well as their shared remembrances of Reggie Stoops (1925 to 1988).

|

| With whom we'll spend substantial time in the other sailing books. |

Bill celebrates his 65th birthday abroad. “In fifteen years he’ll be eighty and I’ll be fifity-three.” reflects Christo. (Bill died exactly fifteen years after the book's publication. Christo's still going strong, although he doesn't seem as active as he once was.)

“Most of my friends I met forty-odd years ago, met them within a radius of two hundred yards of where I’m now standing." (Yale graduation ceremony, 1990) "It occurs to me that forty years is a long time. Less than forty years went by between the day Lincoln was shot and the day Victoria died. Just forty years before we graduated was the year the Chinese abolished slavery, the year Edward VI died as well as William James and Mark Twain. Friendships that last forty years are something. Monuments, I call them, few better grounds for celebration. So let’s toast to the class of 1950."

|

| With some non-matriculators in there as well. |

At one point, Bill gets yelled at by Doug when he goes forward without a lifejacket. This is the same offense he (Bill) yelled at Christo for at the beginning of Airborne. More bookending! It’s not a crisis or anything – it’s a cardinal rule on boats, but I think Bill had his own set of rules, it must be said – and while he concedes he was wrong to do so, I couldn't help but wonder if Doug’s invitations to the Ocean-4 reunions always arrived a day or two late.

SOME THEMES

(1) The book is a reflective affair, as indicated in the subtitle, and part of that reflection has to do with the inevitable widening and hopeful closing of distance between father and son. Part of this theme - reconciliation with Christo (and I probably shouldn't use "Christo," it's just how I got to know him through the books, but it's not like he chose that as his professional name and I should respect that. But that would force me to use "Little" everytime I need to refer to Christopher Little, and I'm trying to avoid just using last names over and over. It feels rude. I almost erased this little aside, but screw it: you need to know this stuff) relates to the other, as that distance is recorded in Christo's terminating the MCI-mail they share. i.e. email/ internet, at that time as much a luxury item as the GPS prototypes they're trying out in these books. An act which he took as a personal affront, as he did his resignation from Bohemian Grove. Equally super-select (then or now.)

(2) I mention the GPS, i.e. the Trimble/ Loran. This brings up one of the most fascinating (and somewhat entertaining, given his exasperation and difficulties with getting the equipment to work consistently, not to mention the lengths everyone goes to to fix things or diagnose the problem) aspects of all Bill’s sailing books, which I always call the Time Travel Tech aspect, i.e. the appearance of new technologies that those well-versed in old ones instantly grasp as revolutionary. (And that we-the-modern-reader might take too much for granted.)

The WhatSTAR stuff is fascinating but a bit impenetrable. (“Was this last sight due to the proximity of Peacock to Rasalhague, less than the tolerable distance between the navigator’s assumed position and his actual position?”) But Bill's excitement with the technology and his inability to get his companions to grasp its revolutionary nature are great fun.

“The Trimble GPS NavGraphic is the ocean equivalent of the postman who knows how to find 22-A Maiden Lane, undistracted by 22 Maiden Lane which is a half-dozen beguiling yards off to the right.

My very first experience with it, sailing into New York from Stamford, was engrossing. I designed the installation so that in inclement weather I could situate the monitor to the navigational miracle on the cockpit, under the dodger. That way we could all actually see ourselves sail, second by second, westward from Stamford, past Execution Rock, up into the East River, past La Guardia Airport and Rikers Island and Hell Gate to Gracie Mansion, and then south down the length of Manhattan.

On the screen, a tiny facsimile of a sailing boat sliding along the illuminated chart, identical to your sailing chart, expanding or diminishing in scale accordingly as you push ZOOM IN or ZOOM OUT, keeping always in front of you the course to your destination and the distance to it, the Estimated Time of Arrival, the Course Made Good – all of those plums to which Loran has accustomed us; but now all there on a live TV screen in front of you. So that when you get to the Brooklyn Bridge your boat is shown under the Brooklyn Bridge – uncanny. Assuming the availability of detailed charts and a disk that covered that part of the world – and all of this will be with us in a matter of a year or so – we’d have glided into Valle Gran Rey as confidently as we slid down the East River.

They certainly have come down from ten thousand dollars in the time since Bill wrote that, and expanded their services considerably.

"The effect of this experience, after about twenty years onboard boats, of trying to cultivate appetites I assumed to be merely dormant, not dead, has melancholy implications. (Classical) music is not a readily addictive drug. And you learn, reflecting on the inventory of cassettes that are the permanent collection of the Sealestial, that there are two very distinct musical cultures out there. The Sealestial's collection is about the size of my own, and although the Nutcracker and the Best of Wagner are there, the balance of the tapes are all of the modern variety, or so I assume, having recognized the names only of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

I like some of the Beatles' music (I don't presume that anybody cares whether or not I do, but there it is); but I had to confess something to Christo a few days later, on the final evening aboard the Sealestial when we came back to the boat from the hotel for the last meal, in the heavy heat of late afternoon Barbados, and I had begun packing my gear. Lo! There was MUSIC issuing of the ship's stereo system. It wasn't my kind of music, but I didn't say anything. After about three minutes, I went to the main unit, removed the tape, inserted one of my own, and went back to my packing. Nobody noticed the change of music - nobody was really listening (...)

It doesn't seem like he kept up this (faking it to making it re: interest in sports) but you can't help but empathize with his plight.

In addition to the Satcom unit aforedescribed, Bill brought "a computer, printer, sea-chest of correspondence, clothes, Scopolamine, Percodan, Antihistamines, Laxatives, Mercurochrome, Saltwater Soap, “and various exotica pressed into my hand by my wife and internist, spare sextant, sextant, chronometer, Air Almanac, plotting sheets, dividers, parallel rulers, HP-41C calculator, stopwatch, HP-249 tables, guidebooks, and assorted Columbiana." This refers primarily to Bill’s out of print copy of Admiral of the Seas, by Samuel Eliot Morison, who was the Navy’s choice to write the official history of WW2 but is somehow considered an untrustworthy source now. Morison merits superficial but scornful mention in Zinn's now-foundational A People's History of the United States, its future-present acolytes to whom Bill unknowingly alludes when he writes “It’s a pity (Morison) is not around to take a role in the celebration of the five hundredth anniversary of Columbus’ crossing. And to take care of Columbus’ critics, a diabolical cult.”

“How did Columbus measure the passage of time? I give you thirty seconds. In Columbus’ days and until the late 16th century the only ship’s clock available was the ampoletta or reloj de arena (sand clock), a half-hour glass containing enough sand to run from the upper to the lower section in exactly thirty minutes. Made in Venice these glasses were so fragile that a large number of spares – Magellan had eighteen on his flagship. I warrant Columbus had some little hour glasses, perhaps gauging the time down to as little as thirty seconds."

VOYAGE’S END

As they near Barbados, Bill rises just before dawn to shoot Jupiter (a trick he learns from Columbus) and predicts they'll sail into Bridgetown Harbor by noon. Not the sort of intelligence Columbus had on his side when making his own journey five hundred years earlier.

As Bill notes, had this happened to Sealestial nothing too terrible would have come of it. (Outside of making Bill Draper nervous on missing his December 5th rendezvous with President Bush.) But had this happened to Columbus, it's likely he wouldn't have survived the trip home. What might have happened to the peoples of the Caribbean then? One of those what-ifs, but more than likely, the exact same thing, just under different sails.

And speaking of those sails, at book's end:

“(As Columbus approached the New World, Morison remarks) 'only a few moments now, an era that began in remotest antiquity will end.' And our own, as well. About fifteen minutes after the appearance of this volume we can expect that navigation at sea will cease to be more than an antiquarian exercise. Probably a couple of flashlight batteries attached to a Trimble hand unit will tell you exactly where you are, day or night.”

No comments:

Post a Comment